Spirits of the Mine

Audio art installation, Narodni Muzej, Battiala-Lazzarini Palace, Labin (2023)

A composition and sound art installation created in remembrance of the 1921 Labin Republic and its unsung heroes, featuring Istrian poet Isabella Flego and musicians Moussa Dembele and Kikanju Baku. The work’s development began in 2021 during a field recording trip to Labin in occasion of the centenary of the short-lived Labin Republic, one of the first worldwide antifascist uprisings. Spirits of the Mine was exhibited in multi-speaker format in the reconstructed underground mine tunnel at the Labin Public Museum as part of the 4th Industrial Art Biennial (May-August 2023).

The installation’s soundscape comprises a reshape of historical recordings of sounds of local coal miners from the Labin Museum archive, interwoven in an electroacoustic composition of environmental and electronic sounds, with kora, balafon and drums, and with readings by Isabella Flego. This spoken word component, recorded at Isabella’s home in June 2022, consists of fragments from her text La Galleria della Memoria and other poems from her books Per ogni domani di cristallo (2022) and Mate Masie (2013), and an extract from Giuseppina Martinuzzi’s poem Presente and Futuro (1900).

Weaving her perceptions during her first visit to the underground mine tunnel at the Labin Museum with memories of her own father, a coal miner, and her grandfather, who took part in ‘the great strike of 1921′, Isabella poetically evokes the experiences, struggles and hardships of the local miners’ community. The soundscape gives presence to this community’s multi-ethnicity, suggesting through a layering and blending of different sonic traditions (concrete, electronic, dub, African and avant-jazz music) a polyphonic present shaped by echoes of multiple people’s histories and cultures. Isabella lived in Ghana for 5 years and wrote about her experience in Memorie sopra l’Equatore. Her haunting poem Il Castello di Elmina, featured at the end of the soundscape, evokes the spirits of African slaves, a reminder of their sufferings and their past and present exploitation within the mining industries in the American and African continents.

Fragments of texts and poems by Giuseppina Martinuzzi and Isabella Flego, selected and read by Isabella Flego for the installation soundscape (with English translation by Carolina Brooks and Anna Piva)

Scava

La negra gallina discende cento metri sotterra

E il lume fioco che dalla volta gocciolante pende

Narra che l’aria va mancando a loco

Scava indefesso

Umil ti piega il fato

Il minerale che ti aspetta giu’, giu’

Di vena in vena

Si noma sua eccellenza il capitale

E innanzi ad esso io ti discerno appena

Figliol della miseria al cristallino fonte ammollisci il negro pane

E sia questo il dritto che leghi il tuo destino

All’imper dell’astuta borghesia

Dig!

The black hen descends a hundred meters underground

And the dim light hanging from the dripping vault

Tells that the air is missing in the place

Dig tirelessly

The fate bends you and makes you humble

The mineral that is waiting for you, down, down

Vein by vein

Is named his excellency the capital

And in front of it I can hardly discern you

Son of misery you soften the black bread at the crystalline fountain

And be this the right that ties your destiny

To the empire of the cunning bourgeoisie

From Isabella Flego’s text la Galleria della Memoria and other poems, in Per Ogni Domani di Cristallo (2022) and Mate Masie (2013).

La Galleria della Memoria

Entro con arcano stupore in un angolo di mondo sotterraneo. Gli occhi si aprono su di esso, entrato in me con emozione dall’interno della rimembranza. Sulle bocche delle pareti indebitate di respiri si posa lo sguardo. Il silenzio al quale sta ancorata la voce di mio padre avanza. Tanto silenzio risale, portando in vita un linguaggio nel midollo della terra generato, fermo sulla faccia dei muri e in ogni altra cosa presente radicato.

Segni erosi e passi incisi sul suolo, dalla poca luce mangiati, riprendono a respirare con il tempo, insieme a tante parole perse nel mondo dentro di me, altre ferme su attrezzi e utensili in sosta che hanno servito viaggi verso smorti orizzonti tra cavità nere e lucide. Anche se superati dal tempo, nel secreto della loro forza muta, hanno in se sul letto di polvere una lingua escoriata che interpretare la può chi l’ha vissuta.

La galleria che mi lascio alle spalle nel fulgor del ricordo di vite passate al piano astrale respira l’eternità, ed è come se dovesse rinascere, ingrandirsi di parole frugate nei pozzi conquistati e persi. Parole della riconoscenza che nessuno cerca più. Parole forti, capaci di sbrecciare la cava, e di codificare il messaggio di ogni voce sepolta nelle crepe della vena nera più profonda.

The Tunnel of Memory

I enter, strangely bewildered, into a corner of the underworld. My eyes open, aware, filling me with an emotion flooded with memories. My gaze rests on the mouths of the walls and their strained breaths. The silence to which my father’s voice is anchored, becomes present. A deep silence surfaces, bringing into life a language generated from the kernel of the earth. It hangs motionless, held in the walls, rooted in the heart of everything.

Eroded signs and steps etched into the ground, absorbed by the faint light, begin to breathe in time along with the many words, lost in the world that I hold inside. Words poised on the abandoned tools and machinery that have served journeys towards the dim horizons among the black and shimmering tunnels. Even when overtaken by time, secret in their silent strength they have embedded a language on a bed of dust, that only those who lived it could understand.

The tunnel I leave behind me with the flash of a memory of past lives, passed onto the astral plane, breathing eternal life as if it should be reborn, become greater through words forged in the mine shafts both conquered and lost. Words of gratitude that no-one utters anymore. Powerful words, strong enough to fracture the walls of the pit and to bring to life the message of every voice buried in the fissure of every black vein.

Ai Minatori

Uscivi dal buio, dalla galleria che nuda si erge

e conduce all’apparir del sole

A passo lento avanzavi, la lampada in mano

Entravi come la luna in cielo stellato nella luce del giorno

La cipria impalpabile che tutto avvolge

Istante sublime, gioia al minatore portata nel cuore

Come fosse l’unica a onorare l’esistenza

e sentire i battiti della vita

Là dove regna sempre la notte vestita di luce da sepolcro,

l’aria grossa tramena

Il gioco di vita e morte alimenta desideri di sole e di mare

Ogni suo soffio prezioso e dolente è respiro

E come un serpente si infila nei polmoni

Fiori di roccia ornati di neri confini

E quando anche la bocca si fa di pietra

Il minatore inventa sorsi d’aria

per l’aurora di un nuovo giorno

To the Miners

You came out of the darkness from the tunnel that stands before you naked

and leads you in to emerging sun

Slowly moving forwards, the lamp in your hand

Arriving like the moon in a starry sky at the light of day

The imperceptible dust that engulfs everything

Transcendent moments captured in the miner’s heart

As if it were the only one to honour its existence and hear the beat of life

There, where night adorned in sepulchral light always reigns

The air hanging heavily

The game of life and death nourishes the desires of the sun and sea

Blowing each breath both precious and piercing

And like a snake it slips into the lungs

Flowers on the rocks decorated with blackened edges

And even when the mouth becomes stone

The miner imagines sips of pure air for the dawn of a new day

Il Castello di Elmina

Intorno al castello l’onda sfiora le rovine

Da ogni pietra l’umidità cola l’avanzo di goccioline di tanti nessuno

Un tempo ugole di canti, di preghiere piene di angoscia

passate alla luce senza monumenti

Nella cella della morte il vento africano spezza appena appena il silenzio dei secoli

Si risvegliano le mura, emananti codici di vita e di morte

Respiro il passato

Inquietanti ombre appaiono e scompaiono

Mi invitano alla tavola del tempo

Per condividere l’antica discendenza

Nell’incontro sconvolgente

La certezza che solo loro, i morti

Hanno conosciuto la fine della schiavitù

The Elmina Castle

Around the castle, the wave touches the ruins

Moisture drips from each stone

The remains of droplets of many nobody

Once uvulas of songs, of prayers filled with anguish

Passed into the light without monuments

In the death cell the African wind hardly breaks the silence of the centuries

I breathe the past

Uncanny shadows appear and disappear

They invite me to the table of time

To share the ancient lineage

In the shocking encounter

The certainty that only they, the dead

Have known the end of slavery

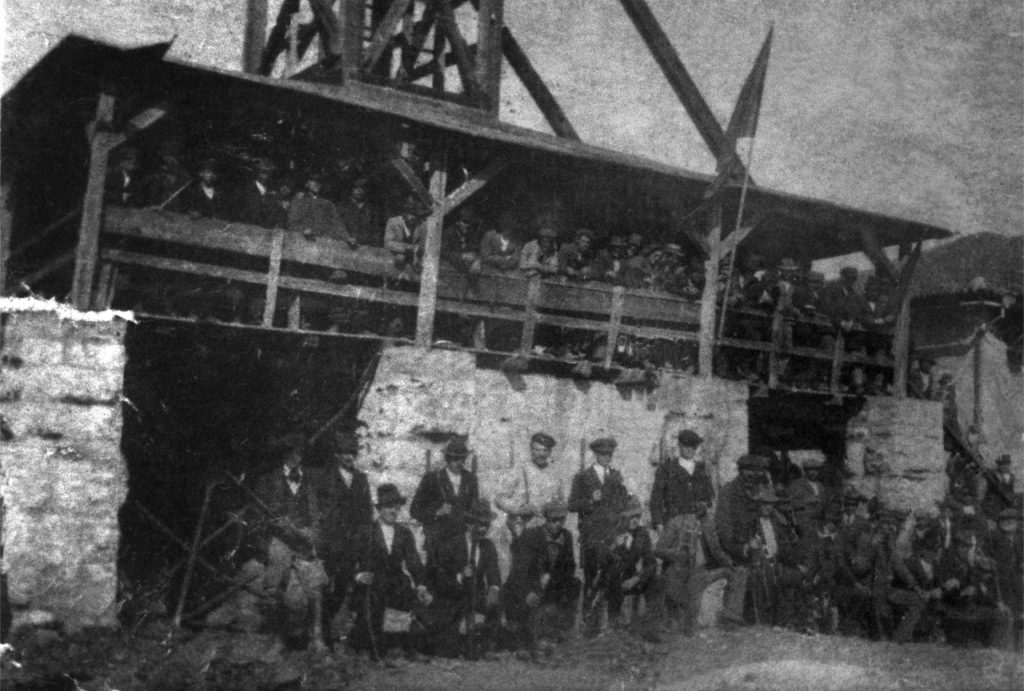

On the Labin Republic

Described by many as the first worldwide antifascist uprising, the short-lived 1921 Labin Republic reverberates in the present as an example of workers’ courage and resistance to the oppressive forces of capitalism and fascism, of self government and active solidarity in diversity.

In the 1920s Istria, previously part of the Austro-Hungarian empire and annexed to the Kingdom of Italy with the Treaty of Rapallo (1920), was home to approximately 2000 miners of different origins: Croatians, Slovenians, Italians, Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Germans and Hungarians.

In 1921 the miners, in response to the inhuman working conditions dictated by the mine’s owners and the increasing violent aggressions by the local fascist squads, occupied the mine and established the short-lived Republic with the support of local farmers. They rigged the entire mining complex with explosives to defend themselves from retaliation by the authorities. They formed a committee as a decision-making body based on the complete equality between different nationalities and mass assemblies for discussion. They successfully managed to continue, and increase the coal production. The strength of their solidarity was tested in the trial that followed the Republic’s violent repression by the army, where they stood strong in their refusal to testify against one another.

The dangers and sacrifices undertaken by this brave community of workers and their struggles for social justice are exemplified by the life of Giovanni Pippan, one of the main protagonists of the uprising. Pippan, an Italian trade union leader from Trieste, had taken the responsibility to voice the miners’ discontent towards the mine’s administration run by the Società Anonima Carbonifera Arsia, and between 1920 and the beginning of 1921 had helped them organise strikes to improve their working conditions.

In Italy 1920-21 came to be known as the ‘Biennio Rosso’. It was a time of economic crisis, unemployment and political instability in the aftermath of World War One. Workers’ protests and strikes occurred throughout the country, also inspired by the initial success of the Russian Revolution and aiming at creating self-management systems similar to the Soviets. These struggles were often repressed with the help of the newly formed fascist squads whose violent criminal activities were secretly supported by industrialists and land owners, and left unpunished by the police and local authorities. In Istria a particularly aggressive form of nationalistic ‘border fascism’ developed, acting through intimidations, beatings, political homicides and other forms of violence against Slovenian and Croatian workers. According to Marina Cattaruzza, during the early 1920s 134 buildings which housed workers cultural centres, cooperatives and organizations were set on fire, including the Narodni Dom in Trieste (13 July 1920) and in Pula (14 July 1920). In September 1920 Mussolini visited Pula, and in a speech declared that ‘In front of an inferior race like the Slavs one must not follow a politics that offers a sweetener, but one that uses the club’.

On 1 March 1921 Giovanni Pippan was severely beaten by a group of fascists at the railway station in Pazin. News of the incident reached the miners in Labin, and in response on 3 March the miners decided to occupy the mine, and proclaimed the Republic with the slogan ‘Kova je naša’ (‘the mine is ours’). The Republic was repressed on 8 April by the army and the police through a surprise violent attack, during which two miners, Massimiliano Ortar and Adalber Sykora were killed and many arrested. In the subsequent trial in November 1921, all miners were acquitted without charges thanks to their solidarity, a strong legal defence and the active support of the local population.

Pippan, whose life had been threatened by the local fascists, was forced to leave Istria and emigrated to the US, where in the following decade he continued organising workers and took active part in the campaign to save Sacco and Vanzetti. In 1931 he moved to Chicago. In 1933 he was assassinated for supporting the local bread distribution drivers’ struggle to free themselves from the Mafia racketeers’ control.

Miners’ struggles and slavery in the US coal mining industry

As in the case o the Labin Republic, in the US the miners’ uprisings during the late 19th and early 20th century were also sustained through class solidarity amongst diverse ethnicities. These struggles against the horrendous working conditions enforced by the mines’ owners and their armed militias were amongst the bloodiest occurring in the country, as described by Mother Jones’, one of the most active miners’ organisers during this time, in her autobiography. In September 1921 thousands of coal miners marched to unionize in West Virginia, resulting in a deadly clash and the largest U.S. armed uprising since the Civil War.

Since its very beginnings, the US coal industry utilised African slaves’ labour. Historical records show that the earliest coal mining of any commercial significance involved slaves working in the coal pits in the vicinity of Richmond, Virginia in the mid 1700s. A form of slavery continued until the early 20th century in the US through the use of convict labour. A concerted effort was made to arrest Black people, issue excessive sentences, and then lease them to coal mining companies.

Slavery in the mines didn’t end after the war in 1865. For decades prisoners convicted of “vagrancy” and “loitering” worked as virtual slaves for private outfits in Alabama, Georgia and Tennessee. From 1880 to 1904, 10 percent of Alabama’s state budget was paid by leasing prisoners to coal companies. African Americans accounted from 83 percent to 90 percent of these slave miners in Alabama. Sixty-nine percent of Tennessee prisoners digging coal in 1891 were Black. Some poor whites were railroaded to jail too.

Conditions were horrendous in these convict mines. Nearly one out of ten prisoners died annually at the Tracy City, Tenn. mine operated by the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company (TCI). TCI was bought by United States Steel in 1907. USS continued to operate TCI’s mines in Alabama for another 20 years. Reparations are owed by USS and the JPMorgan/Chase Bank whose financial ancestor set-up this steel Goliath as the first billion-dollar corporation in 1900.

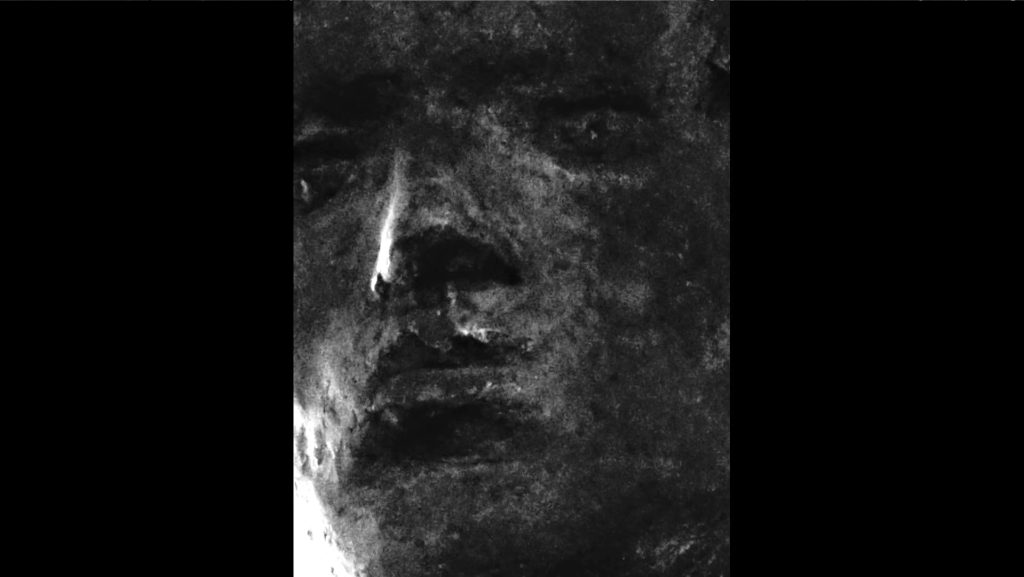

A 90 year-old ex-slave miner, West Virginia, 1921

(Source: Workers’ World online)

James Knox, an African American convicted of passing a $30 bad check, was tortured to death by guards at Alabama’s Flat Top mine on Aug. 14, 1924 because he was unable to meet the mine’s daily ten-ton quota.

Three hundred miners with guns freed prisoners at TCI’s Briceville, Tenn. facility on July 15, 1891. The following week 1,500 miners returned to free more prisoners. H.H. Schwartz of the Chattanooga Federation of Trades reported that “whites and Negroes are standing shoulder to shoulder” and armed with 840 rifles.(from Stephen Millies’ Black Coal Miners – A long legacy of struggle, 2006)

Sources:

For the history of the Labin Republic, see La repubblica di Albona e il movimento dell’occupazione delle fabbriche in Italia by Giacomo Scotti and Luciano Giuricin, in Quaderni, Volume 1, Centro di Ricerche Storiche – Rovigno (1971); Balcani: “La miniera è nostra!” Storia della Repubblica di Albona, by Riccardo Celeghini, online at https://www.eastjournal.net/archives/71072 (retrieved on 12/9/2020); The Republic of Labin, 1921 by Steven Johns (2017), online at libcom.org; La Repubblica di Albona, by Tullio Vorano, online at

https://www.istrapedia.hr/it/natuknice/58/la-repubblica-di-albona

For an introduction on the history of African American coal mining slaves in the US, see The Darkest Abode of Man: Black Miners in the First Southern Coal Field, 1780-1865 by Ronald L. Lewis (The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 87, No. 2, April 1979, pp. 190-202). Also see Black Coal Miners in America by Ronald L. Lewis (The University Press of Kentucky, 1987) and Coal, Class and Color, Blacks in Southern West Virginia, 1915-1932 by Joe William Trotter, Jr. (University of Illinois Press, 1990); Black Coal Miners – A long legacy of struggle by Stephen Millies, online at workers.org.

For more on present slavery, child labour and human rights abuse in African mines, see the Free the Slavers’ Investigative Field Report online (https://freetheslaves.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Congos-Mining-Slaves-web-130622.pdf) and Siddharth Kara’s book Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives (2023).